On of my favorite pesonalities from Americanhistory is Benjamin Franklin. In my opinion, he should be at or near the top of everybody's list. Here is my reposting of the segment of this remarkable man from my Profiles of Leadership in America:

America is known as a place of opportunity, as a place where one’s genius can be developed and given a chance to be productive and, possibly, benefit mankind. In its youth, America was much the same, with entrepreneurs and visionaries exploring the possibilities. The British Government had settled its colonies in America for economic and strategic reasons, but the British subjects that actually came to these shores were seeking freedom to be what they wanted to be, to be free from perceived religious, political, and economic shackles. During the 17th and 18th Centuries, America was seen by many without opportunity as a place where a “nobody” could become a “somebody”. And, in some special cases, they could become a very important and universally celebrated “somebody”, like Benjamin Franklin.

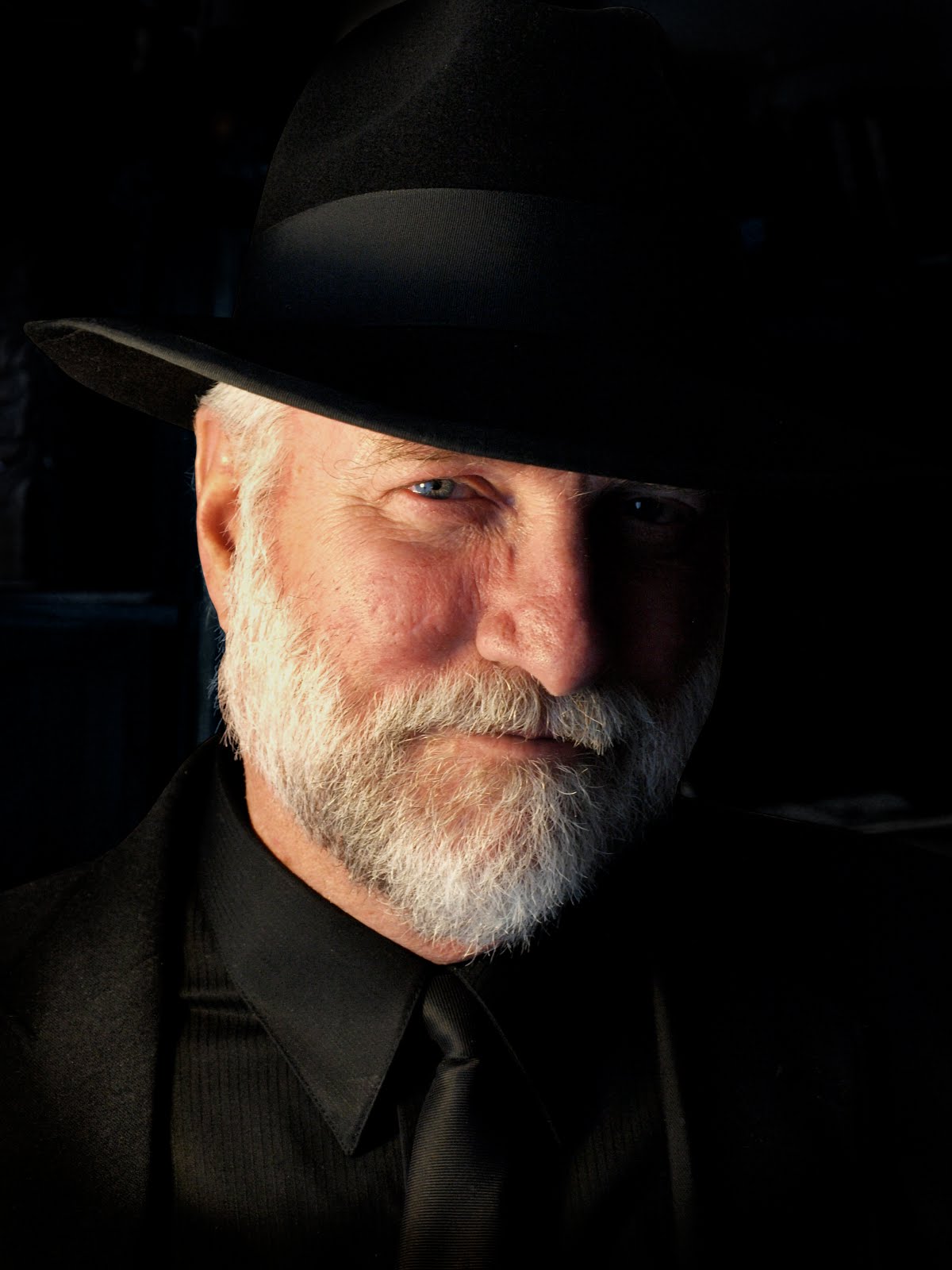

Benjamin Franklin

January 17, 1706—April 17, 1790

There are few people, if any, in today’s world who compare with Benjamin Franklin. In fact, there are few people of any age that compare with Benjamin Franklin. He was a writer, publisher, scientist, inventor, educator, politician, statesman, diplomat, philosopher, patriot, and philanthropist. No one, who did not serve as President of the United States, has influenced our country for the better more than Benjamin Franklin.

Born in Boston in 1706, Franklin was the 15th child and youngest son of Josiah (a soap and candle maker) and Abiah Franklin. He only attended school for two years and did not do well enough that his father felt he could afford to further educate him. His father kept young ten years old Benjamin home to work in the family shop. His schooling may have stopped but he continued to educate himself by reading every book he could lay his hands on, believing that, “the doors of wisdom are never shut” (Eiselen 413). Franklin did not like the soap and candle trade, so his father sent him to be apprentice to his older brother James, a printer. Franklin proved to be a skilled printer, but he frequently argued with his older brother. Franklin was secretly writing some popular articles under the pen name “Mrs. Silence Dogwood” that James was publishing. When James discovered that his younger brother was writing the articles, he refused to print any more of them. Franklin ran away at age 17 to Philadelphia and at age 24 opened his own shop and started publishing The Pennsylvania Gazette, writing much of the material himself. He also married Deborah Read that same year with whom he had two sons (William became governor of New Jersey) and a daughter.

As a printer–writer-publisher, Franklin developed his newspaper into the most successful one in the colonies. As a businessman he was innovative. Historians credit him as the first to publish a newspaper cartoon and to illustrate news stories with a map. He was even more successful with his publication of Poor Richard’s Almanac, which he wrote and published for 25 years. In the almanac he preached much of his philosophies of virtue, industry, and frugality with memorable wise and witty sayings such as, “Early to bed and early to rise, makes a man healthy wealthy and wise.” “God helps them who helps themselves.” “Little strokes fell great oaks.” And “He that falls in love with himself will have no rivals” (Eiselen 413).

Although Franklin never actively sought public office, civic leadership was constantly thrust upon him. In 1736 he became clerk to the Pennsylvania Assembly and then agreed to be Philadelphia’s postmaster. His work as postmaster so impressed the British government that, in 1753, they offered him the position of deputy postmaster general of all the colonies. Franklin improved the postal service throughout the colonies and even Canada. He worked constantly to improve his city by establishing the world’s first subscription library, organizing a fire department, reforming the city police department, starting a program to pave and light the dirty city streets, and raised money to build a hospital. By these efforts, he helped Philadelphia to become the most advanced city in the British colonies.

As a scientist and inventor, Franklin was inexhaustible and completely philanthropic, choosing not to patent or benefit financially from his many inventions. One of the first men in history to experiment with electricity, Franklin proved, with his famous kite experiment of 1752, that lightning was electricity. He used this knowledge to invent the lightning rod, urging others to use his device to protect their lives and property. Once, he tried to electrocute a turkey only to shock himself unconscious. He later remarked, “I meant to kill a turkey, and instead, nearly killed a goose” (Eiselen 415) (Perhaps this is the real reason that he esteemed the turkey above the eagle as a symbol for The United States). Other inventions that benefited his fellow man were his fuel-efficient stove design and the bifocal glasses. Once, after viewing the first successful balloon flight in France, he heard bystanders scoffing, “What good is it?” Always a forward thinker, Franklin responded, “What good is a new born baby?” (Eiselen 415).

In 1754, when the French and Indian War broke out, Benjamin Franklin offered a plan for the colonies to unite to defend themselves. He printed the famous cartoon of a disjointed snake with the caption, “Join or Die.” His ideas for “one general government” that was presented to a conference in Albany would later find its way into the Constitution of the United States. Though his plan failed to be ratified, Franklin worked hard to support the British army in its fight against the French and their Indian allies, securing horses, wagons, and other supplies and equipment while raising volunteer armies to help defend frontier towns.

When friction started to develop between Britain and her colonies after the French and Indian War, Franklin worked to keep the colonies British, while protecting what he believed were the colonies rights. In 1757, Franklin was sent by the Pennsylvania legislature to London to lobby parliament in respect to tax disputes. For most of the next 18 years until 1775, he remained in Britain as an unofficial ambassador representing the American point of view. Franklin preferred that America remain in the British Empire, but only if the colonists’ rights were protected. He pledged to pay for all of the tea destroyed in the Boston Tea Party if Parliament would only repeal its tax on tea. His proposal was rejected and he returned home two weeks after the American Revolution had begun.

Again, Franklin was chosen to serve in the Second Continental Congress, where he again proposed a plan (similar to the Albany Plan) to unify the colonies, which laid the groundwork for the Articles of Confederation. He was chosen to again organize the postal system, which he quickly accomplished, giving his salary to the relief of wounded soldiers. He helped Thomas Jefferson draft the Declaration of Independence and signed it, declaring, “we must indeed all hang together, or assuredly we shall all hang separately” (Eiselen 415b). Later that year (1776) at age 70, Franklin left for France where he would, as ambassador, eventually charm the French into joining the Americans against the British. Without Franklin’s success in securing the help of France, the American Revolution would likely have failed.

After the war Franklin returned to Philadelphia and served as president of the executive council of Pennsylvania (Governor, basically) and attended the Constitutional Convention. He was instrumental, by his wisdom and common sense, in keeping the delegates from going home when negotiations got sticky. At his suggestion, the delegates prayed, at the beginning of each day of business, for spiritual guidance. Franklin declared, “…without his (God’s) concurring aid, we shall succeed in this political building no better than the builders of Babel; we shall be divided by our little, partial, local interests, our projects will be confounded, and we ourselves shall become a reproach and a by-word down to the future ages” (Benson 18).

Franklin was proud of what his country had accomplished. He had personally signed the four major documents in early American history; the Declaration of Independence, the Treaty of Alliance with France, the Treaty of peace with Britain, and the Constitution of the United States. He even hoped that the example of the Americans would lead to a United States of Europe. But, Franklin knew that much was left to do. Two years before his death, he was elected President of the first anti-slavery society in America. His last public act was to appeal to Congress to abolish slavery.

He had accomplished many marvelous things in his lifetime. He was a great man that did many great things and was greatly loved. In 1789, (one year before Franklin’s death) George Washington wrote in a letter to Franklin, “If to be venerated for benevolence, if to be admired for talents, if to be esteemed for patriotism, if to be beloved for philanthropy, can gratify the human mind, you must have the pleasing consolation to know that you have not lived in vain” (Eiselen 416). In his will, Franklin simply wrote of himself, “I, Benjamin Franklin, printer…”(416).

References:

Article on Benjamin Franklin by Malcolm R. Eiselen from the World Book Encyclopedia 1970.

This Nation Shall Endure by Ezra Taft Benson.

America is known as a place of opportunity, as a place where one’s genius can be developed and given a chance to be productive and, possibly, benefit mankind. In its youth, America was much the same, with entrepreneurs and visionaries exploring the possibilities. The British Government had settled its colonies in America for economic and strategic reasons, but the British subjects that actually came to these shores were seeking freedom to be what they wanted to be, to be free from perceived religious, political, and economic shackles. During the 17th and 18th Centuries, America was seen by many without opportunity as a place where a “nobody” could become a “somebody”. And, in some special cases, they could become a very important and universally celebrated “somebody”, like Benjamin Franklin.

Benjamin Franklin

January 17, 1706—April 17, 1790

There are few people, if any, in today’s world who compare with Benjamin Franklin. In fact, there are few people of any age that compare with Benjamin Franklin. He was a writer, publisher, scientist, inventor, educator, politician, statesman, diplomat, philosopher, patriot, and philanthropist. No one, who did not serve as President of the United States, has influenced our country for the better more than Benjamin Franklin.

Born in Boston in 1706, Franklin was the 15th child and youngest son of Josiah (a soap and candle maker) and Abiah Franklin. He only attended school for two years and did not do well enough that his father felt he could afford to further educate him. His father kept young ten years old Benjamin home to work in the family shop. His schooling may have stopped but he continued to educate himself by reading every book he could lay his hands on, believing that, “the doors of wisdom are never shut” (Eiselen 413). Franklin did not like the soap and candle trade, so his father sent him to be apprentice to his older brother James, a printer. Franklin proved to be a skilled printer, but he frequently argued with his older brother. Franklin was secretly writing some popular articles under the pen name “Mrs. Silence Dogwood” that James was publishing. When James discovered that his younger brother was writing the articles, he refused to print any more of them. Franklin ran away at age 17 to Philadelphia and at age 24 opened his own shop and started publishing The Pennsylvania Gazette, writing much of the material himself. He also married Deborah Read that same year with whom he had two sons (William became governor of New Jersey) and a daughter.

As a printer–writer-publisher, Franklin developed his newspaper into the most successful one in the colonies. As a businessman he was innovative. Historians credit him as the first to publish a newspaper cartoon and to illustrate news stories with a map. He was even more successful with his publication of Poor Richard’s Almanac, which he wrote and published for 25 years. In the almanac he preached much of his philosophies of virtue, industry, and frugality with memorable wise and witty sayings such as, “Early to bed and early to rise, makes a man healthy wealthy and wise.” “God helps them who helps themselves.” “Little strokes fell great oaks.” And “He that falls in love with himself will have no rivals” (Eiselen 413).

Although Franklin never actively sought public office, civic leadership was constantly thrust upon him. In 1736 he became clerk to the Pennsylvania Assembly and then agreed to be Philadelphia’s postmaster. His work as postmaster so impressed the British government that, in 1753, they offered him the position of deputy postmaster general of all the colonies. Franklin improved the postal service throughout the colonies and even Canada. He worked constantly to improve his city by establishing the world’s first subscription library, organizing a fire department, reforming the city police department, starting a program to pave and light the dirty city streets, and raised money to build a hospital. By these efforts, he helped Philadelphia to become the most advanced city in the British colonies.

As a scientist and inventor, Franklin was inexhaustible and completely philanthropic, choosing not to patent or benefit financially from his many inventions. One of the first men in history to experiment with electricity, Franklin proved, with his famous kite experiment of 1752, that lightning was electricity. He used this knowledge to invent the lightning rod, urging others to use his device to protect their lives and property. Once, he tried to electrocute a turkey only to shock himself unconscious. He later remarked, “I meant to kill a turkey, and instead, nearly killed a goose” (Eiselen 415) (Perhaps this is the real reason that he esteemed the turkey above the eagle as a symbol for The United States). Other inventions that benefited his fellow man were his fuel-efficient stove design and the bifocal glasses. Once, after viewing the first successful balloon flight in France, he heard bystanders scoffing, “What good is it?” Always a forward thinker, Franklin responded, “What good is a new born baby?” (Eiselen 415).

In 1754, when the French and Indian War broke out, Benjamin Franklin offered a plan for the colonies to unite to defend themselves. He printed the famous cartoon of a disjointed snake with the caption, “Join or Die.” His ideas for “one general government” that was presented to a conference in Albany would later find its way into the Constitution of the United States. Though his plan failed to be ratified, Franklin worked hard to support the British army in its fight against the French and their Indian allies, securing horses, wagons, and other supplies and equipment while raising volunteer armies to help defend frontier towns.

When friction started to develop between Britain and her colonies after the French and Indian War, Franklin worked to keep the colonies British, while protecting what he believed were the colonies rights. In 1757, Franklin was sent by the Pennsylvania legislature to London to lobby parliament in respect to tax disputes. For most of the next 18 years until 1775, he remained in Britain as an unofficial ambassador representing the American point of view. Franklin preferred that America remain in the British Empire, but only if the colonists’ rights were protected. He pledged to pay for all of the tea destroyed in the Boston Tea Party if Parliament would only repeal its tax on tea. His proposal was rejected and he returned home two weeks after the American Revolution had begun.

Again, Franklin was chosen to serve in the Second Continental Congress, where he again proposed a plan (similar to the Albany Plan) to unify the colonies, which laid the groundwork for the Articles of Confederation. He was chosen to again organize the postal system, which he quickly accomplished, giving his salary to the relief of wounded soldiers. He helped Thomas Jefferson draft the Declaration of Independence and signed it, declaring, “we must indeed all hang together, or assuredly we shall all hang separately” (Eiselen 415b). Later that year (1776) at age 70, Franklin left for France where he would, as ambassador, eventually charm the French into joining the Americans against the British. Without Franklin’s success in securing the help of France, the American Revolution would likely have failed.

After the war Franklin returned to Philadelphia and served as president of the executive council of Pennsylvania (Governor, basically) and attended the Constitutional Convention. He was instrumental, by his wisdom and common sense, in keeping the delegates from going home when negotiations got sticky. At his suggestion, the delegates prayed, at the beginning of each day of business, for spiritual guidance. Franklin declared, “…without his (God’s) concurring aid, we shall succeed in this political building no better than the builders of Babel; we shall be divided by our little, partial, local interests, our projects will be confounded, and we ourselves shall become a reproach and a by-word down to the future ages” (Benson 18).

Franklin was proud of what his country had accomplished. He had personally signed the four major documents in early American history; the Declaration of Independence, the Treaty of Alliance with France, the Treaty of peace with Britain, and the Constitution of the United States. He even hoped that the example of the Americans would lead to a United States of Europe. But, Franklin knew that much was left to do. Two years before his death, he was elected President of the first anti-slavery society in America. His last public act was to appeal to Congress to abolish slavery.

He had accomplished many marvelous things in his lifetime. He was a great man that did many great things and was greatly loved. In 1789, (one year before Franklin’s death) George Washington wrote in a letter to Franklin, “If to be venerated for benevolence, if to be admired for talents, if to be esteemed for patriotism, if to be beloved for philanthropy, can gratify the human mind, you must have the pleasing consolation to know that you have not lived in vain” (Eiselen 416). In his will, Franklin simply wrote of himself, “I, Benjamin Franklin, printer…”(416).

References:

Article on Benjamin Franklin by Malcolm R. Eiselen from the World Book Encyclopedia 1970.

This Nation Shall Endure by Ezra Taft Benson.

No comments:

Post a Comment