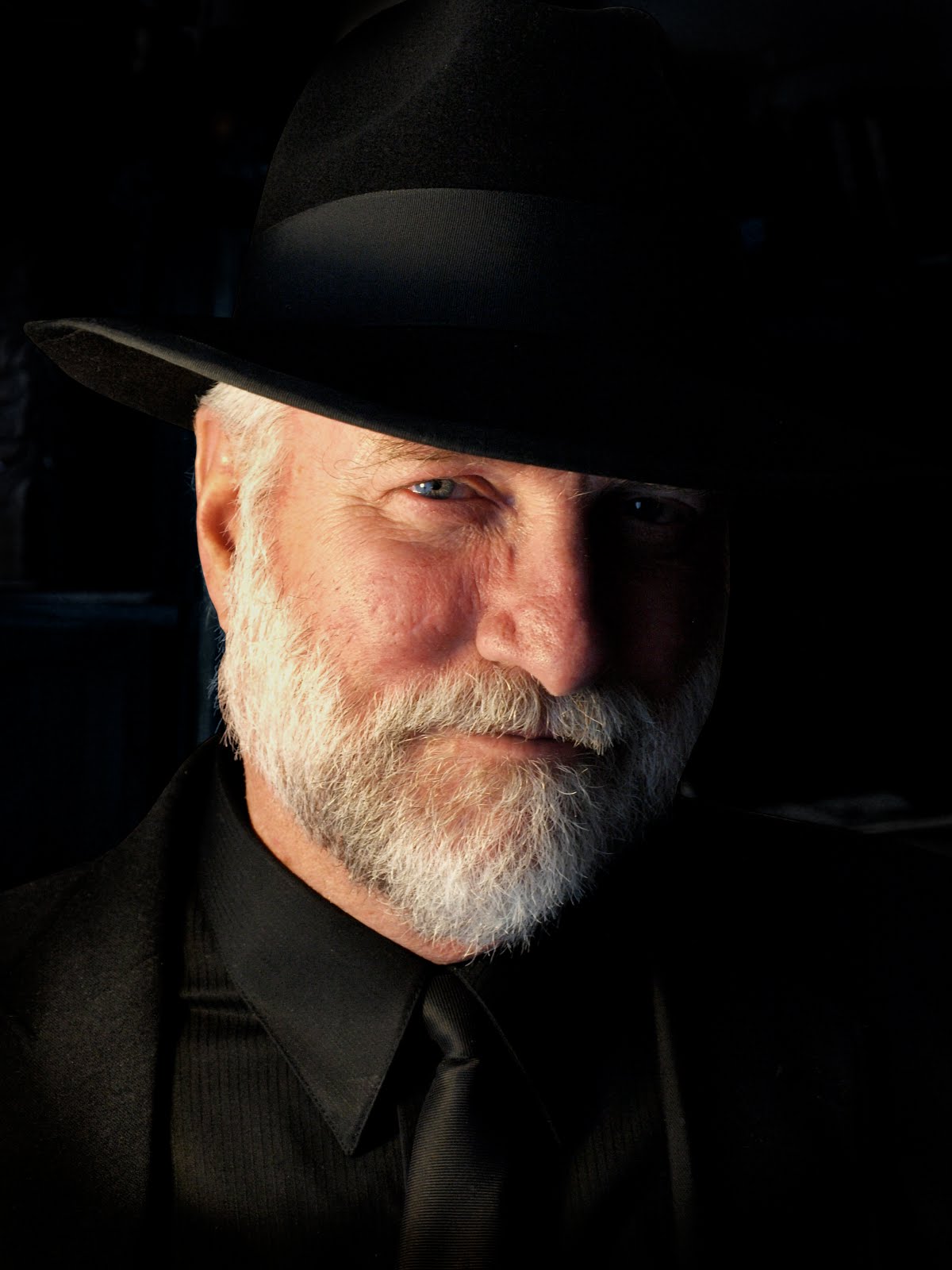

William Penn

October 14, 1644—July30,1718

When one visits the Statue of Liberty in New York harbor they can read the famous lines written by Emma Lazarus:

“Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breath free, the wretched refuse of your teeming shore, send these, the homeless, tempest-tossed, to me: I lift my lamp beside the golden door.”

During the 17th Century when religious outcasts (many of which were tired and poor) were seeking asylum from persecution, there were few, if any, such places in the world as Emma Lazarus describes. However, a young convert to Quakerism, William Penn did envision such a place, and planned to make it happen in America.

Penn was the well-educated son of wealthy Admiral Sir William Penn. Though he came from a well-to-do family, Penn was attracted to the teachings of the radical preacher, George Fox. Against his father’s wishes, Penn joined with the Society of Friends (Quakers) and became one of the faith’s most ardent defenders. During his career, he was arrested and imprisoned several times for his religion, but he never relaxed his faithfulness to it.

Quakers believed that the Holy Spirit or “Inner Light” was capable of inspiring everyone (even women). They had no paid clergy and no official creed. These beliefs plus the fact that most of the Quakers were of the bottom wrung of the social ladder and chose not to tip their hats to the social elite, made the Quakers extremely unpopular in England.

Although he was not the typical Quaker, William Penn’s personal experience with religious persecution, his sense of right and wrong and his religious faith prompted him to provide a safe haven for his fellows. Using his own great personal wealth and calling in on a debt owed by King Charles II to Penn’s father, Penn was able to secure a land grant in North America which was named Pennsylvania. Penn founded and designed the city of Philadelphia (city of Brotherly Love). He created a government with more than the usual democracy, hoping to limit the “power of doing mischief, that the power of one man may not hinder the good of the whole company.” He, like Roger Williams before him, treated the Indians fairly and wished to live with them as neighbors and friends. And again, like Roger Williams, he enlarged on the image of America as a freedom-loving place and provided much of the philosophy that would later be borrowed by the architects of the Constitution of the United States. Before his death, Penn wrote his “Essay Towards the Present and Future Peace of Europe”, in which he outlined a plan for a league of nations based on international justice.

Though William Penn spent limited time in his colony and he died a virtual pauper in England, he left a great legacy and a great vision for the future. Not only did Quakers from England, Germany, The Netherlands, and Wales flock to Pennsylvania, but Presbyterians, Baptists, Anglicans, Lutherans, and Catholics were attracted to Pennsylvania’s religious toleration as well. And though Penn’s “peaceable kingdom” eventually suffered from the absence of his leadership, during his time, he lifted his “lamp beside the golden door.”

No comments:

Post a Comment