As Americans pushed their way across the continent of North America, they inevitably pushed the Indians along the way, and few of the American Indians were particularly happy about it. Though the outcome was obvious to many, there were some who refused to go away quietly in the night. And, unlike great leaders of Sacajawea’s nature, who embraced the coming Americans, some Indian leaders chose to resist the tide by heroic though futile effort, and by so doing wrote their names in history as great. Thus was Tatanka Iyotanka.

.jpg)

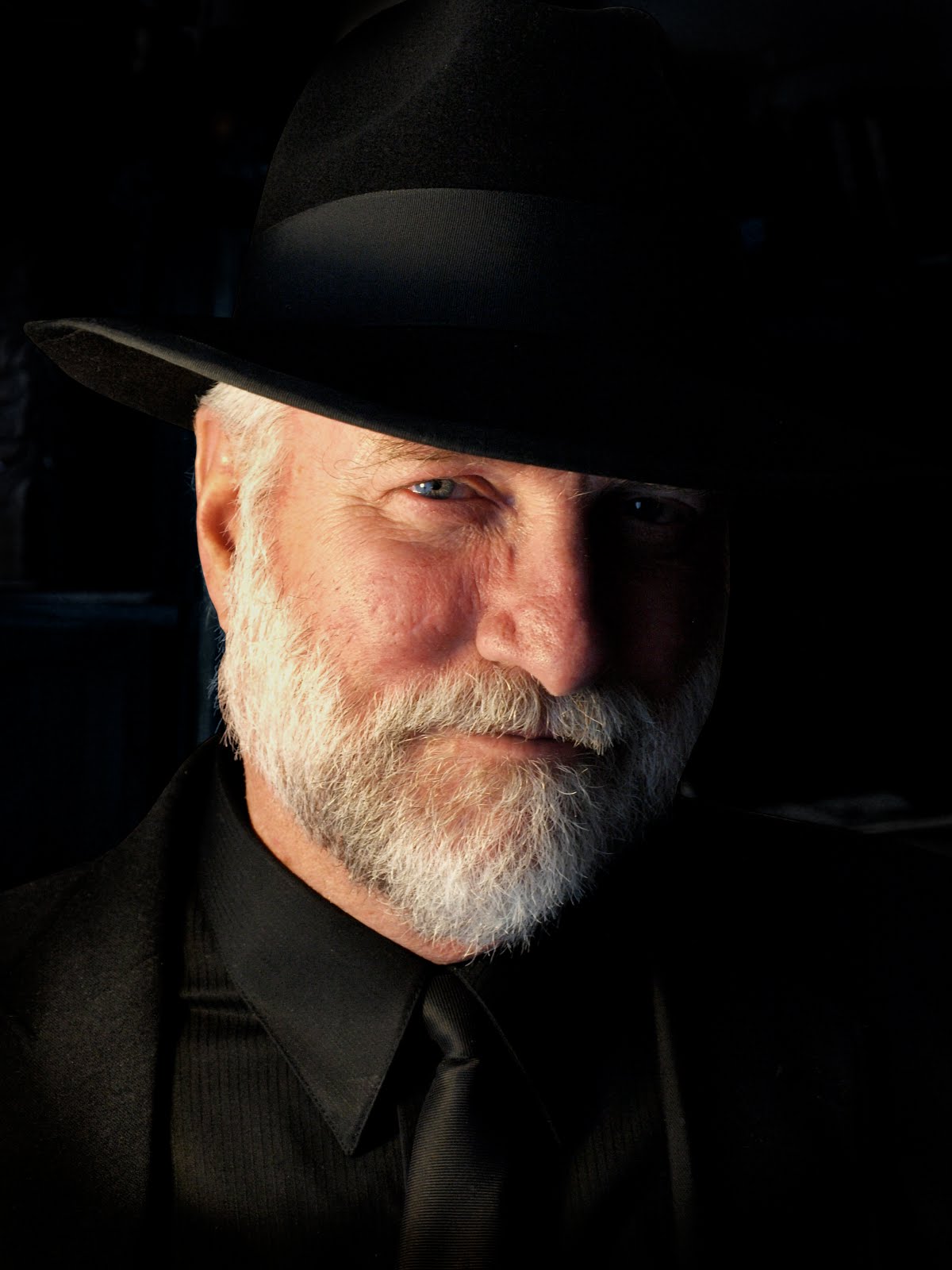

Tatanka Iyotanka (Sitting Bull)

C. 1831—December 15, 1890

Tatanka Iyotanka, or Sitting Bull, as most of us know him from history was the Hunkpapa Lakota Sioux holy man credited with providing a premonition of victory over the US Cavalry that resulted in the defeat of George Armstrong Custer and his men at the Battle of the little Bighorn. To many of white America at the time of the Indian wars with the US Cavalry, he was the bad guy. But he was a great leader to his people and later became an American icon and major attraction in Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show.

In truth, he spent most of his adult life fighting the American Whites, trying to stem the tide of the white people’s continued incursion into Indian lands. Sitting Bull gained early notoriety fighting the American settlers and soldiers as a result treaty violations by the United States during the 1850s and 1860s. When the Dakota Sioux fled Minnesota into Dakota lands to escape the US forces, Hunkpapa Lakotas, with the young Sitting Bull came to their aid in reprisals against white settlements in Minnesota. In the early 1860s Sitting Bull likely fought in the Battles of Dead Buffalo Lake, Stony Lake, Whitestone Hill, and eventually Killdear Mountain. In each case the Indians were defeated and the majority forced to surrender, but Sitting Bull and other diehards like him continued to fight on, striking immigrant wagon trains and impeding the railroads’ progress through Indian lands. He was again a major player in the Red Cloud War of the later 1860s using guerilla tactics against US troops and whites in general. When a treaty was again reached in 1868, he refused to agree to live by it.

His continued resistance against the whites during the early 1870s gained him much respect among the various Indian tribes and ultimately gained him a leadership role when, in 1876, new hostilities erupted between the Sioux and the United States. After gold was discovered in the Black Hills, Sitting Bull and his followers attacked white settlers and gold prospectors. The US armed forces were sent into the Dakota Territory to capture Sitting Bull and force his renegades back to their reservations. The advance force of the US Army, the 7th Cavalry under the direction of Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer, caught up to Sitting Bull and his followers on the 25th of June, 1876 at a village on the Little Bighorn River. Unbeknownst to Custer, the holy man, Sitting Bull, had made it known among the Indian tribes of the region that he had had a dream of a great victory over the American soldiers—he saw the soldiers falling into the village like grasshoppers and being killed. The holy vision had convinced thousands from various local tribes to desert their reservations and join in the coming fight. The result was one of the greatest victories of Indians over US forces. Custer and his immediate command were killed, and while the remnants of the 7th Cavalry licked their wounds in retreat and under siege waiting for the rest of General Terry’s command to arrive, Sitting Bull and forces escaped.

Ultimately, the tribes were forced back onto their respective reservations, but Sitting Bull, still not willing to concede defeat and ignoring offers of pardon took his followers into Canada. By 1881, Sitting Bull had had enough and returned with 185 of his people to surrender. He lived without much excitement, going where ever the authorities ordered him to go until 1885, when he accepted an offer by Buffalo Bill Cody to join his Wild West Show. As a member of Cody’s show for almost two years he established himself as a major draw and was paid the goodly sum of $50 per week. People wanted to see the infamous Indian Warrior who defeated Custer and they were willing to pay large sums for his autograph.

During his time with Cody’s show, Sitting Bull gained a new appreciation for the magnitude and power of the American people. When he returned to his home on the reservation, he realized that there was no going back to the old ways. Any new efforts to fight against the Americans would mean total destruction for his people. The few years prior to Sitting Bulls death were largely uneventful; the Sioux tribes tried to make their livings as farmers and struggled with the dry soil of the Dakota Territory. However, by 1890 there began be some interest by younger Indians in the Ghost Dance rituals. It was feared by some in the department Of Indian Affairs, that the Ghost Dances would encourage new uprisings of hostility among the Indians on the reservations, so thousands of additional soldiers were moved into the area. Thinking that Sitting Bull might be influencing this new behavior, the authorities decided to take him into custody. During Sitting Bull’s arrest by Indian policemen, a friend of the holy man fired and killed an arresting officer and further shots were fired on both sides. When the gunfire ended, Sitting Bull and several on either side lay dead.

Though not considered a hero to much of the nation at the time, Tatanka Iyotanka was a hero to his immediate followers and an inspiration to many, to a degree, on both sides of the conflict between the Indians and the Americans. He must be recognized for his leadership qualities and his loyalty to his people and his desire for their protection. In the end, he had come to realize, like other great leaders of his race, that it was fruitless to defy the odds and that the preservation of their people meant eventual assimilation. Like all great leaders he fought the good fight against great odds, and when defeat was imminent he accepted defeat graciously to save his followers from starvation. Sadly, his death was unnecessary and tragic, but his life was to be admired.