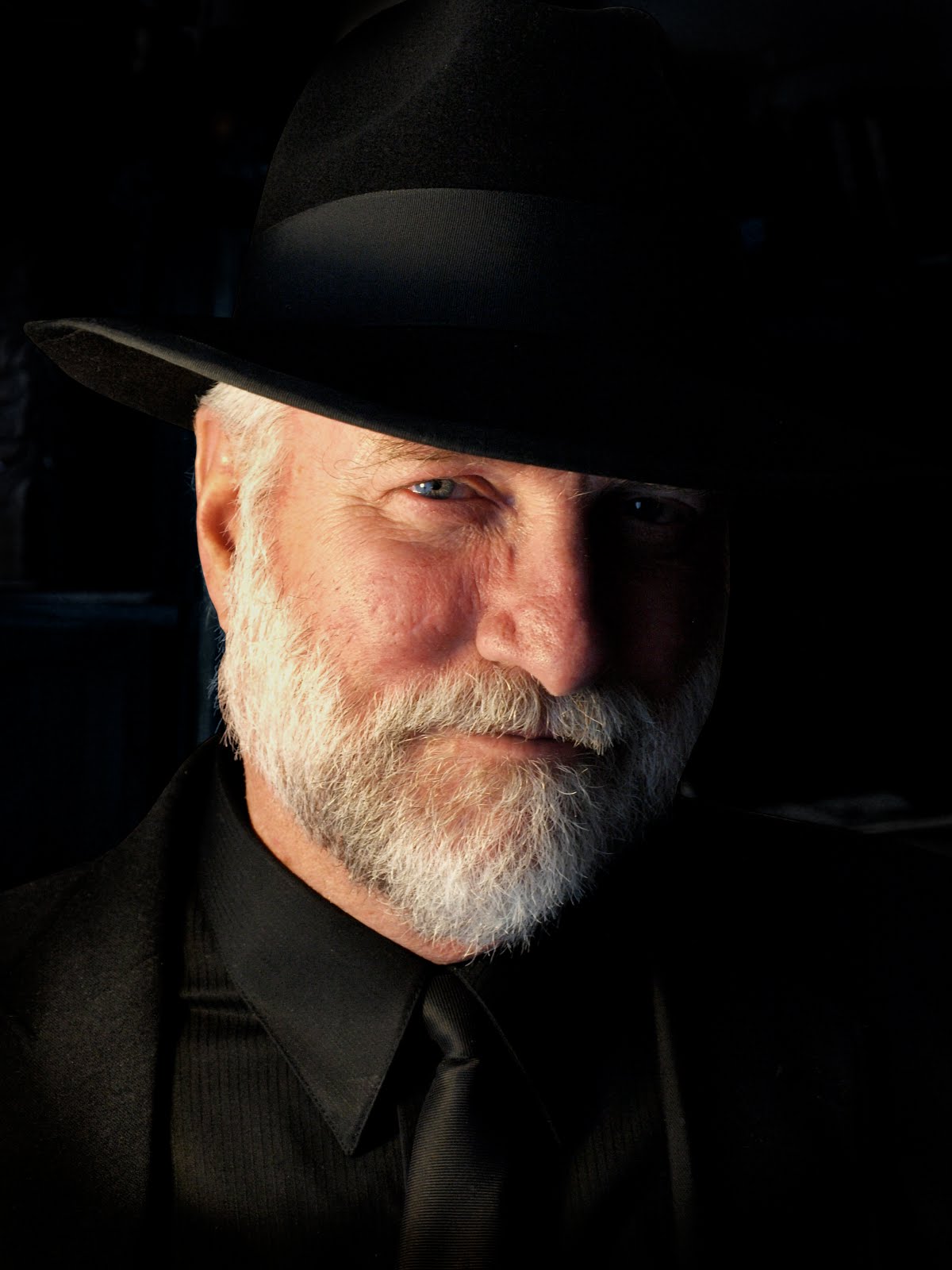

Frederick Douglas

February 1818—February 20, 1895

Throughout the history of the United States, many individuals, both black and white, have struggled with the practice and the legacy of slavery. Many tried to end the practice of slavery before and during the American Civil War and many have tried to correct the evil effects of slavery in its aftermath. However, perhaps no one man in our country’s history has had as powerful an impact on the subject of slavery as Frederick Douglas.

Douglas was born a slave in Maryland around the year 1818 but escaped to the North in his early twenties. An extremely bright and well-self-educated man, he became the voice of the enslaved black man in the North. Through his speeches and written narratives about his life experiences as a slave, he educated northern whites about the immorality of slavery. He was able to give intelligent first hand witness, as no white abolitionist could, of the murders, rapes, beatings, and other various acts of inhuman cruelty heaped upon fellow humans because of their skin color.

The institution of Slavery, according to Frederick Douglas, was destructive for both the black slave and the white slave owner. Slavery reduced the blacks to the social position of farm animals or beasts of burden. Blacks could be bought and sold at the whim of their masters. The slaves life was full of hardship and it was not his own. They might be beaten, maimed or even killed at the slightest provocation. White slave owners, because of their embrace of slavery, were necessarily hypocrites to their professed Christian beliefs. Adultery, rape, and even murder were practices rationalized by some (slave owners) to be within the slave owner’s property rights. Because of the influences of slavery, slave owners became cruel and uncivilized, to the point of treating their own flesh and blood children (products of sexual unions between masters and slaves) as chattel. If not cruel and unfeeling at first, the white master could eventually succumb to the slavery mentality and perform acts of cruelty.

In the Narrative of the life of Frederick Douglas, Douglas describes the misery of his childhood as a slave. Douglas laments the fact that he never knew his birth date and his actual age. This was not uncommon. “By far,” writes Douglas, “the larger part of the slaves know as little of their ages as horses know of theirs, and it is the wish of most masters within my knowledge to keep their slaves thus ignorant (p.1).” Douglas was equally ignorant of his father’s true identity. Douglas was separated from his mother when he was still an infant (not unlike a puppy that has been weaned) so was unable to have his mother clarify the matter. But, he understood from those around him that his father was a white man and it was rumored that it was Douglas’ master.

Douglas describes the insecurity and instabilities of the slave’s life. Slave children on the Farms in Maryland, according to Douglas, seldom had enough to eat or enough to wear. He recites, “I suffered much from hunger, but much more from cold. In the hottest summer and coldest winter, I was kept almost naked (p. 16).” “The children unable to work in the field had neither shoes, stockings, jackets, nor trousers, given to them; their clothing consisted of two coarse linen shirts per year (p. 6).” Slave men and women were allowed a monthly supply of food that consisted of eight pounds of pork or fish and a bushel of corn and a yearly set of clothes consisting of two shirts, two pairs of pants, a jacket, a pair of socks and a pair of shoes. The slave’s allotment of food and clothing, in most cases, was only designed to keep the slave alive and healthy enough to work.

A slave lived constantly under the threat of physical harm or of being separated from family and loved ones. Douglas, as a small child, witnessed the savage whipping of his “Aunt Hester” for disobeying her jealous master’s orders to stay away from a male slave friend. “If a slave was convicted of any high misdemeanor, became unmanageable, or evinced a determination to run away,” writes Douglas, “he was… severely whipped, put on board the sloop, carried to Baltimore, and sold… as a warning to the slaves remaining (p. 6).”

Douglas believes that not only did the slave suffer from the effects of slavery but that the humanity of the white slave holder also suffered. The institution of slavery created a generation of hypocrites through out the “Christian” White South. Douglas explains that it was some how deemed, by slaveholders, to be biblical and thus acceptable before God to enslave a race of people (descendants of Ham). Douglas reported that when one of his masters attended a Methodist camp-meeting, Douglas felt hope that experiencing religion would prompt his master to emancipate his slaves or at least make him more kind and humane. “If it had any effect on his character, it made him more cruel and hateful in all his ways…he found religious sanction and support for his slave holding cruelty (p. 32).”

The institution of slavery suggested the right of the slave owner to do whatever he or she might want with their property. Many slaves, as Douglas suspected he might have been, were conceived by white masters. “I know of such cases;” says Douglas, “and it is worthy to remark that such slaves invariably suffer greater hardships, and have more to contend with than others (p. 2).” The white father, according to Douglas, feared to treat their mulatto offspring as their own children and in deference to the feelings of their white wives would often put their own children on the auction block.

Douglas records several instances of punishment that escalated to murder. In one case, an overseer by the name of Gore whipped a slave named Demby until the slave fled for the safety of a nearby creek. When the frightened slave refused to come out of the water to receive the rest of his punishment the “cool and collected” Mr. Gore raised his musket to Demby’s face and fired, instantly killing the poor slave. In another case, a Mrs. Hicks savagely beat a young teen-age slave girl with a stick, breaking her nose and breastbone in the process, for falling asleep while caring for Mrs. Hicks’ baby. The young slave died within hours of the beating. Douglas allows that these two crimes may have created some sensation in the local community, but he laments that the murderers in both cases were not brought to justice for their crimes.

Douglas believes that the basically kind and humane are equally subject to the corrupting influence of slavery. When Douglas encounters a new mistress who had never previously owned a slave he was impressed with the kindness that she showed him. She seemed disturbed by the “crouching servility” that he habitually exhibited towards her. She patiently taught him to read. She was unlike any other white woman he had known. “But, alas!” declares Douglas, “this kind heart had but a short time to remain such. The fatal poison of irresponsible power was already in her hands, and soon commenced its infernal work. That cheerful eye under the influence of slavery, soon became red with rage… and that angelic face gave place to that of a demon (p. 19).”

Douglas believed that the practice of slavery inhibited the progress of both Blacks and Whites in America. Douglas’ first hand testimony of the suffering of black men and women trapped in the institution of slavery is a powerful indictment against it. However, he also believed the degradation and suffering of the enslaved was equaled by the degradation, inhumanity, and hypocrisy embraced by the enslaver. Douglas felt that the white slave holders, because of the effects of slavery, had turned their backs on their fellow man and in so doing denied the God that they professed faith in. He compares those that embrace slavery to those hypocritical “scribes and Pharisees” that Christ describes in the Bible “which strain at a gnat and swallow a camel (p.73).” He foresees the time that God will let the guilty be punished. Again quoting the Bible, Douglas declares, “Shall I not visit for these things? saith the Lord. Shall not my soul be avenged on such a nation as this (p. 74).”

During the Civil War, Douglas used his influence as a popular speaker and writer to lobby the United States Government to free southern slaves and to allow his fellow black men to fight for the Union Army. President Lincoln eventually did issue the Emancipation Proclamation and ordered that black infantry units be formed. These black infantrymen fought bravely in several battles that proved to be crucial victories for the North.

During the reformation years and until his death in 1895, he continued to be an important voice in America. Still a prominent speaker and writer, Douglas lobbied the Government to protect the rights of the newly freed Black men and women of the South. Because of the influence of Douglas and men like him, the 13th, 14th, and 15th amendments to the constitution, outlawing slavery and recognizing citizenship and the right to vote for blacks, were ratified. Douglas went on to exemplify what blacks, given the opportunity, could accomplish. He was appointed secretary of the commission to San Domingo in 1871, presidential elector in 1872, marshal for the District of Columbia in 1879, and United States minister to Haiti in 1882.

An example of leadership and hero to Americans of all races, Douglas pulled himself up from slavery and ignorance and refused to forget his fellows that still suffered. Before, during, and after the Civil War, his life was spent calling for justice. He clarified, to many blacks and whites alike, the true meaning of the words penned by Thomas Jefferson, “We hold these truths to be self-evident: That all men are created equal…”

No comments:

Post a Comment